"The four types of icon" by Vladislav Andrejev

If we believe that the icon simultaneously expresses the visible and the invisible worlds, we will see that there is more than one dimension to iconology. When examined with this belief in mind, an icon painted on wood, termed “hand-created icon,” cannot have independent meaning. To appreciate its true significance, it is necessary to pass through all of the layers of the life of the body, soul, and spirit which are only symbolically touched upon by the icon. Additionally, having discovered a reflection of the ultimate possibility of the Knowledge of God in icon-writing, we must uncover the strictly theological basis for icon-writing, and its true source, its Archetype.

When the icon is examined from the point of view of the Christian Church, a symbolization of four universal layers of existence will be seen to develop: Cosmos—the purely material and bodily state, the physical world; Anthropos—man, the state where material and spiritual are united into one; Theocosm—the spiritual, bodiless, “noetic” state of intelligence, the Angelic Hierarchy; and Prosopon—the uncreated World of the divine iconography of the Logos, the Idai, and the Eide, according to which the created world is “icon-painted” into existence by the will of God.

The Righteous St. John of Damascus, in summarizing the experience of the holy fathers concerning the icon as “image of God’s action,” points us in the direction of seeing four main types of “icon”:

(1) The “theological,” as according to the Hypostases of God;

(2) The “iconological,” according to the Prosopon;

(3) The “anthropological,” according to the image of created noetic and bodily beings (angel and man).

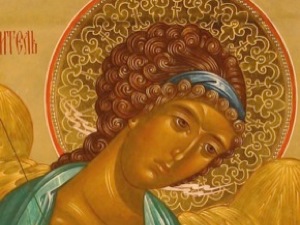

(4) The “cosmological” or “symbolic,” namely the hand-painted icon, whose iconography has two aspects: a) the historical/personal—the iconographic portraits of Christ the God-Man, holy men and women, and angels. b) the theological/didactic—the ideas depicted in the icon through symbol and allegory for purposes of instruction about dogma, the commandments, and prayer.

Divine Revelation is in essence one, for “both depiction and word have one and the same role... For that which the word of speech offers to the hearing, silent painting presents to the eyes through imitation.”

“In many parts and in manifold forms spoke God from of old in His prophets.” Not only did He speak, but He appeared to the holy fathers in manifold fashion as well, in one or another “image of action.” In tradition, we find a mystical distinction between hearing and sight. The two concepts are necessary for the strengthening of faith because both constitute one truth of faith. Moses says, “the Lord spoke unto you out of the midst of fire: you heard the voice of the words, but you saw no image.” Moses himself, however, both heard the voice of God and beheld His angelic Image which was speaking from out of the burning bush. But a new Image, a new Icon of the rarest theology appeared to the world with the incarnation of the Son of God. Christ is not only the Word of God, but the Image of God which revealed God the Father. As this Logos-in-Image, He did not merely take up human flesh as a garment, but became man to the fullest extent. “For the Logos did not dwell within man, but became man.” Christ within the “anthropological” icon “is a living Image and the immutable imprint of the invisible God.” By His humanity, Christ the new Adam revealed Himself to be truly the Icon of the invisible God. The beginning of man’s salvation is the inception and establishment of the “paradisiacal image of action,” icon-writing.

The icon is first of all an “image of holiness, a triumph and a declaration...” God is Holy and has created man in imitation of Himself. Man is “earth,” “land,” though “holy land,” for “the Glory of God has shone upon it,” and this is what was pointed out to Moses on Mt. Sinai. The relationship between Godhead and humanity is multiform, “multi-imaged,” and occurs according to and through “image,”—not through “essence” (ousia). God requires holiness from man who was created according to His Holy Image, His Prosopon. “Be holy; for I the Lord your God am Holy [within My Image, My Icon].” It is holiness according to God’s Image that defines man’s intended state—a created image of the uncreated Image of God within the holiness of union. Only from within the holiness of the Icon as original principle can man worthily glorify God. The height and power according to which man is called “a lesser God,” or “a God by grace” are given to man precisely through the union of these two natures, the Image of God and man’s created image. In this state, man is an icon of the Divine Actions.

The correct conditions for the Presence of God on earth are created through glorification—“praise God in the heavens”—and the Incarnation of God continues to occur through a kind of icon-writing. The Lord says, “I will glorify those that glorify my name.” And so, the icon, if understood in its significance of being the Revelation of God, discloses many depths of ascent, or of approach to the Essential Prosopon of God, wherein lies the Divinization, Theosis, of the age to come.

This is the Church Tradition which has been developed by the holy confessors and defenders of the icon, and by iconographers, contained within rules called “canons.” The violation of canons leads to the distortion of the consciousness of the dogmas of faith, and this faith soon “materializes” into humanistic and naturalistic forms and conceptions about God. Thus the “religious painting,” which merely contains elements of the religious, is born. Its level is moralistic, not theological, for it stimulates only the discursive mind of the believer and does not provide the truth of experience necessary for the deepening of faith. “We beseech the people of God, the holy people, to keep firmly the traditions of the Church. For the disregard of insignificant traditions, as with stones of a building, soon leads to the collapse of the entire structure.”

“The Image of the invisible is itself invisible, for otherwise it would not be an image.” Only the person practicing icon-writing—the art of iconography or the real icon-writing of one’s image in life—strives to make the invisible visible, “for any image is a revelation and exposition of a hidden Archetype.” An “image” is only relatively invisible, until the point at which it is given a symbolic form of visibility. The concepts “visible” and “invisible” ought to be viewed by means of “differentiation” or “distinction” within a unified whole: they should not be “divided” from each other as being polar opposites. For the noetic life of the invisible world is one with cosmic, visible life, and the divine Life of uncreated Light is in union with our life, according to the immutable Forethought of God. “And so, we also desire to see that which can be seen.”

“It was God Himself who first created an image, for He created the first man according to the Image of God [according to the Archetype which is the Prosopon]. Abraham, and Moses, and Isaiah, and Daniel, and all the prophets saw the Image of God, and not the Essence of God itself.” This “Archetype is the very thing which depicts itself, and from which a copy is made.” For this reason God warned Moses: “see that you create everything precisely according to the Prototype which was shown to you on the mount.” And this is why the Hebrews venerated the Tent of the Covenant in every location, for it was the reflection of the Heavenly Tent (Shekhinah or Greek skene), the Prosopon. And the law of the Old Testament is the antechamber of the coming New Testament Image of Service, in which the Grace which makes man an icon elevates him to the “uncreated Jerusalem on high, ‘whose builder and maker is God,’ since everything was done for the sake of [that Jerusalem]: both that which was set up by the law, and that which corresponds to our service.”

A creative confession of faith is an icon-writing in word and in color. “There is no nature [physis] existing without hypostasis, and no essence without image [prosopon].” Thus the fathers of the Church, without dividing “word” from “image,” instruct to “depict in image the unspeakable condescension of God, His birth from a Virgin, the Baptism in the Jordan, the transfiguration on Tabor, the passions which produce passionlessness, the miracles—symbols of His Divine Nature accomplished through the action of the flesh, the saving tomb of the Savior, His Resurrection, His Ascension into the heavens—write everything both in word and with paints, in books and on boards.”

“Word” is “light,” and the form of “light,” the “garment” of “light,” is “color.” “Theology in color” exists alongside “theology in word.” These are two vitally acting principles of faith in man, but they each have a distinct goal of realization. Taking both directions within the framework of true religious dogma, we will distinguish conditionally between them as between two directions of faith. One is the ascending, apophatic movement of “word”—theology, the path of simplification and poverty of spirit, the putting aside of any naming of God, the path of wordless presence before the magnificence of the Glory of God. The other is the descending, cataphatic movement of “color”—iconology, the path of ontological complication and the carrying out of oikonomia, the path of the awe and delight of creativity, conversation with God and attribution of names to God. The “word” seeks in complete asceticism to remove any name or title from God, but strives to approach the meaning of existence. “Color” seeks to incarnate God and clothe Him in the vestments of appropriate names and attempts to bring material and noetic symbols closer to each other within the beauty of coexistence with God: “and because man consists of soul and body, it is impossible for us to reach the noetic unless the bodily be the means.”

In the ideal, both modes of movement should occur simultaneously, without bias towards one or the other, for man is at once a spiritual and a material being whose movement is simultaneously oriented both upward and downward. This is an ideal, dogmatic definition of the essence of man, however. The problem arises when movement begins to lean uniformly downward, to the excessive, heavy “materialization” of consciousness. However, the opposite tendency, an excess of upward motion, is also possible and brings a “false spiritualism,” prelest’.

“To a creature of reason belong two faculties: the contemplative [theological] and the active [iconological]. The contemplative faculty comprehends the nature of being; the active reflects upon [designs] deeds and determines for them the correct [symbolic] measure.” The active faculty—icon-writing—which searches for special forms, the “garments” for invisible things, is called by St. John of Damascus “good reason” and “beauty of wisdom,” as also is said in the Eucharistic Canon: “You have said unto Your Wisdom: let us make man.” Through appropriate symbolic form, the invisible is fulfilled and incarnated in the icon. “By faith we understand that all is brought from non-existence into being by the [icon-painterly] power of God.” Should we not also in imitation “icon-paint” the Revelation of God, bringing it out of hidden mystery into ready contemplation?

This Revelation is not only the Being of God in the Hypostases, but also the Life of God within the Prosopon, which contains the entire Forethought and Counsel of God, the ideas and archetypes, the Paradigms. These desire to gain their symbolic form, their eidos, by participating in the life of created beings. Similarly, the icon “according to essence,” i.e. the “hypostatic” image, depicts historical people and events in accordance with Scripture. And the icon “according to life,” the “eidal” image, depicts the ideas of salvation and divinization in accordance with Tradition and the ascetic experience of prayer. “Hypostatic” images are “pre-defined in the fore-knowing Counsel of God before the ages, presented and pre-announced in the various forms and words of the prophets by the Holy Spirit,” as for instance, is the image of the person of the Virgin Mary Theotokos. But the “eidal” forms of the ideas of salvation are changeable in form and are developed by the Tradition of the Church depending on our potential to accept them, and the strength of our faith.

The apophaticism of the soul’s ascent to the spirit and the cataphaticism of the descent of the soul to the body (but only after the soul has united itself with spirit)—the scale of this simultaneous motion within the span of the Knowledge of God—enables us to speak of many forms of Revelation, about the types of “icon.” Out of these, we will examine in detail the four all-encompassing “images” of the Knowledge of God brought to light by the Tradition of the Church, mainly drawing on the experience of the defenders of the icon and the witness of St. John Damascene.

(1) The first type of “icon”—the “theological icon”

This is the Trinity’s Image of Being, contemplated by the mind, according to the Hypostases.

We can view this first type of “image” in two sub-categories: a. the natural—God within Himself, the Being of God—His Essence, incomprehensible and invisible to both word and color; b. hypostatic, according to “position and imitation,” the Image of Tri-Hypostatic Being.

This first type of “icon” is an icon “thought in word” only. The capacity to think about God is planted within the mind of man and lies at the core of creation which is “according to the likeness of God.” Man “theologizes” with thought—this is also an icon-writing. The possibility of such thinking about God exists due to the special mystical “issuing forth” or “stepping out” or “nearing” of God, Theophany, and the mind of man is capable of seeing these issuings, by depicting (“image-ing”) them within itself.

The first stepping forth of God from His unknowable Nature is His first icon-written Image. The Fathers have categorized it as the “Image of God’s Being” within the three one-in-Essence (i.e. one according to Being) Hypostases. God as Hypostasis is an image—the “Image of His Being.” This is the general, initial point of any possible definition of God. Further, within intra-Trinitarian relationships, theology finds a development of this general concept and singles out specific cases of this “theological icon”: one Hypostasis reveals another Hypostasis in Image.

Thus, the “prime, natural, and unchanging [theological] Image of the invisible God is the Son of the Father.” The Son is “the brightness of His Glory, and the express Image of [the Father’s] Hypostasis.” “The Son is the natural, unchanging Image of the Father, like unto the Father in everything except unbegotten-ness and fatherhood.” Within Himself, however, the Son is not only “the Image of the Father,” but God, and an independent Hypostasis, who doesn’t lose His personal Image of Being in the process of showing the Image of the Father. The Son, “He that Is within the Image of God,” took on an historical image and the likeness of man, while still remaining the perfect Image of the Father. “The Son is the Counsel, Wisdom, and Power of the Father; the Son of God became man for the purpose of returning to man his Image and Likeness, for which sake man was created.”

Furthermore, the third Hypostasis, the Holy Spirit, He who points to the Son and reveals Him in His breath, is the Image of God the Son. But according to His Image of Being, the Holy Spirit is a Hypostasis of God. The living Breath of the Hypostasis, whose principle is “procession” from the Father, is the Image of the Son. For God is understood not only as an “absolute,” but as the Father alive in the Spirit and living in the Son. And so, “the Son is the Image of the Father, and the Image of the Son is the Spirit, through which Christ, abiding in man, gives to man that which corresponds to the Image of God [to the Icon]. The actions of the Holy Spirit are called “spirits” or “energies” and it is necessary to distinguish these actions from the Actor Himself, the Ekporeutos.

Thus we see the “theological” type of icon, the icon which is mentally “thought” about the one God in the Trinity:

The Father’s Image of Being is the unbegotten and unoriginate Hypostasis, which reveals the idea of the Trinity’s oneness of Essence;

The Son’s Image of Being is the Hypostasis which through Wisdom discloses and reveals God the Father;

The Spirit’s Image of Being is the Hypostasis which life-creates through Love and discloses and points to the Son.

Through the miracle of Hypostatic Theophany, the theology of the contemplation of the entire Trinity through intelligence becomes a possibility. “The Hypostases stand and dwell one within another; for they are inseparable and irremovable one from another, unconfusedly fitting inside each other, but unmixed and unconfused. And their movement is one and the same, for their one-in-essence direction is one.